Leading the fight to preserve Surety Bail for bail agents in California

COSTS OF BAIL REFORM

One of the many arguments used by proponents of Bail Reform has been around the cost savings provided by alternative release mechanisms.

Bail reform efforts often lead to drastic changes in the processing of criminal defendants. Due to additional procedures and steps necessary for law enforcement under these types of reforms, officers are routinely kept off the streets and tied to their desk for hours processing just one defendant. County budgets are impacted with additional mandatory court hours, additional judges, a robust pretrial services division, monitoring equipment purchases and maintenance, and the list goes on.

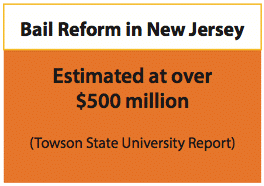

In fact, counties in New Jersey led a lawsuit claiming an “unfunded mandate” after bail reform began in January of 2017, only to lose by a technicality and not on the merits of the case. The counties claimed that bail reform would cost millions to implement, and it did. In just one year, the New Jersey judiciary has stated that the courts will run out of money to fund the program and must need millions in additional taxpayer money. This, despite 2 years of planning and $130 Million in reserves to begin the program.

There“really is no “jail bed” savings calculation that can be attributed to eliminating “money bail.”

Proponents have long claimed that by eliminating “money bail” and implementing a robust pretrial services agency, a county can save millions of dollars. They calculate this figure by taking the total cost of a jail, dividing it by the number of days in a year, and then dividing it by the number inmates in a day. Far from scientific, this simple calculation is supposed to represent a day cost per jail bed. Every person they release for free can then be multiplied by the cost per jail bed and you have your savings.

The problem with this type of calculation is that most of jail costs aren’t variable, but rather they are fixed. Letting one person out of jail does not save money because costs are not based on occupancy in that way. The corrections officers must still be paid, housing costs for the facility must still be paid, and the food must still be bought. It costs the same to guard a 1⁄2 empty jail pod as it does a fully occupied jail pod – minus a few meals. The only way you save money in a jail is by closing a wing or an entire jail, which rarely happens under reform efforts due to most jails operating at near capacity already.

Another fault in this type of cost analysis is that jail population numbers are not constant. They are making the false assumption that if someone is let out of jail, the bed they are removing him from is now empty and they have no “bed cost,” thus a savings. Once again, the reality of this scenario simply doesn’t add up. Jail populations are not static, they are very much fluid. If a jail bed is freed up, it is not left empty but rather filled up by another inmate. As you can see, there“really is no “jail bed” savings calculation that can be attributed to eliminating “money bail.”

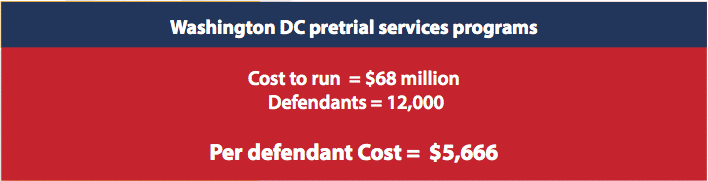

In the process of explaining to people how much money the pretrial programs can save (which of course, they don’t), proponents rarely talk about how much these pretrial programs cost – perhaps for obvious reasons.

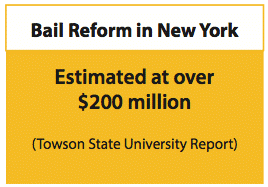

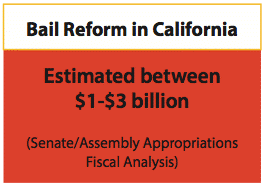

Other states have done costs analysis of pretrial programs and economists have reported their findings on potential costs to implement the no-money bail system.

Reforming the bail system in any jurisdiction will only happen at great cost to taxpayers and cannot be dismissed – especially when these proposed reforms have unintended consequences that threaten public safety and criminal accountability.

Regardless as to the degree any proposed changes to the bail system a jurisdiction is legislatively willing to go, it is incumbent upon lawmakers and stakeholders to understand the social impact to the communities they serve.